The return of haze pollution in the region is cause for shock and concern. In recent weeks, air quality in parts of Malaysia and Indonesia has been poor and over the weekend, Singapore’s readings hit the unhealthy range for the first time since 2019.

The haze has recurred frequently since the severe fires of 1997, but a recent interregnum of blue skies lulled many into thinking the problem was resolved.

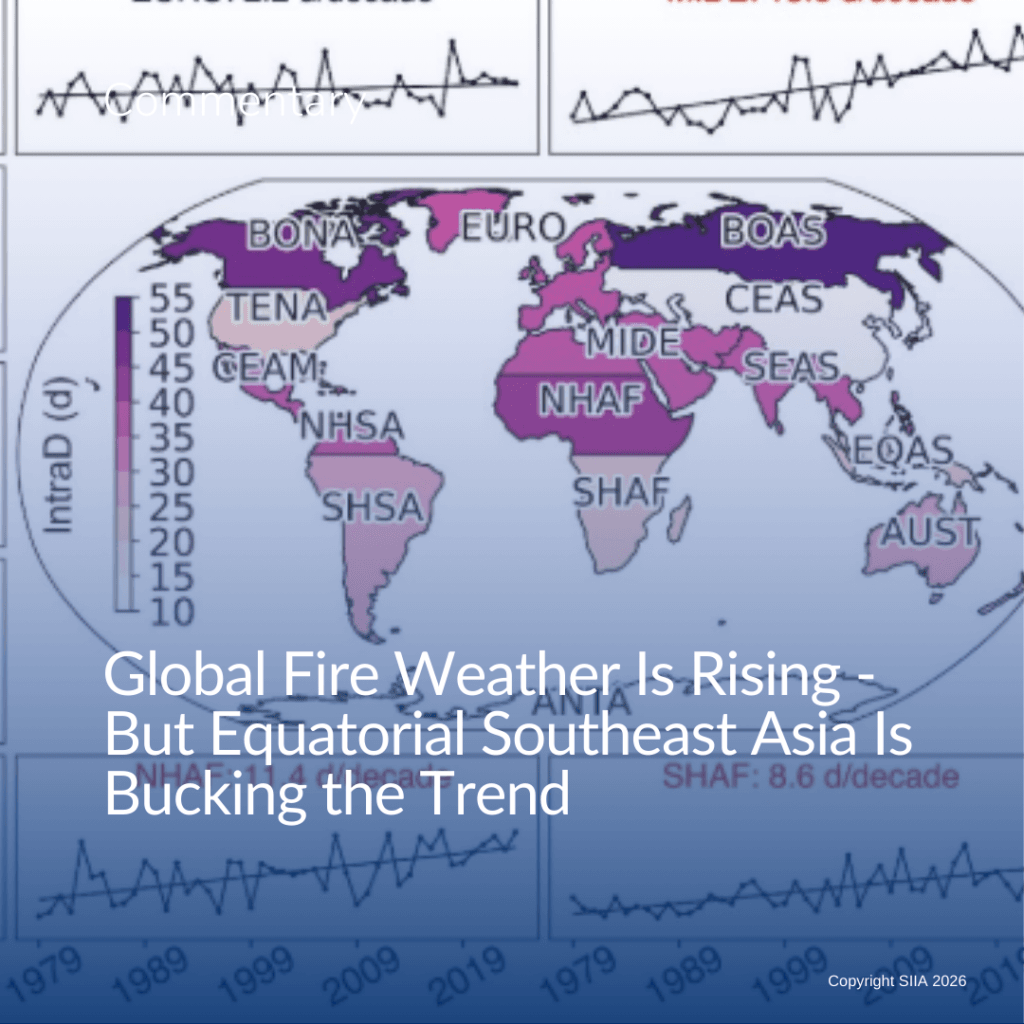

In June 2023, the annual Haze Outlook issued by the Singapore Institute of International Affairs (SIIA) sounded a “red” alarm about the risk of severe haze returning. At that time, the weather was still wetter than normal. But a major factor shaping the assessment was indeed the variable weather. The intersection of El Nino and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole, where sea temperature changes affect air pressures over the Pacific and Indian Oceans, is deepening and extending the dry season.

SIIA sounded that alarm to call attention and nudge governments and companies to make preparations. In recent weeks, SIIA has also engaged officials, corporations and experts in countries key to the issue – Indonesia and Malaysia.

The unhelpful blame game

Who is to blame? Some are already pointing fingers. Malaysia’s Minister of Natural Resources, Environment and Climate Change Nik Nazmi blamed the haze hitting his country on fires from beyond his borders. The Indonesian authorities have rebutted this and suggested that problems stem from companies controlled by Malaysians. Among companies with plantation holdings, most are silent or point the finger to smallholders clearing land through fires that then run out of control.

The Indonesian authorities are now taking action – not only in firefighting and disaster management, but also in investigating suspects and employing an array of legal sanctions. Last week, Indonesian officials announced they are preparing legal action, including bringing possible criminal charges against 11 companies in Sumatra that had fires on their land.

These companies hold sizeable properties in areas that can impact Singapore and Malaysia with haze, given wind patterns. Within Sumatra, the provinces of Jambi and South Sumatra have seen the most fires in 2023. More companies are being investigated in Kalimantan and other fire-prone areas. In total, over 200 companies have been warned.

Even before this, the Jokowi administration has given attention to the issue and taken unprecedented efforts. These include a permanent moratorium on granting new permits for businesses to clear primary forest and peatland and creating Manggala Agni, a nationwide fire brigade that also trains local police and fire rangers.

Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry has been enlarged and empowered. Minister Siti Nurbaya Bakar, who is in charge of the ministry, has served both terms of the Jokowi administration and is acknowledged to be effective and willing to take on companies and others to achieve her goals.

On the basis of these and other reforms, President Joko Widodo, also known as Jokowi, declared the end of fires and haze to be one of the legacies of his time in office.

It is clear the Jokowi government has done more than any earlier Indonesian government. But it is just as clear that these efforts are insufficient to fully resolve the problem.

We should acknowledge the dominant factor that has changed in 2023: the weather. Yet, this acknowledgement cannot be a blanket excuse for inaction.

Tackle haze now

It is wrong to see the haze as a short-lived nuisance.

In previous haze years, fires peaked in September, clearing up by October with monsoon rains. But meteorologists are warning that with El Nino and the Indian Ocean Dipole, dry conditions will likely persist into late October or even November and fire risks will continue.

Moreover, these weather phenomena often extend across multiple years. Climate change may also reduce the interval between these events.

The challenge of fighting fires is real and must be an ongoing concern, with an eye on underlying factors in the resource and agribusiness sectors and another on how the haze worsens the impact of Indonesia’s carbon emissions that contribute to climate change.

The political climate in Indonesia is also changing. Most immediately, with the upcoming general election to form the next Indonesian government, some local officials tend to relent on strict enforcement in order to court votes. There are already reports of some provinces giving more attention to the issue than others.

For the longer term too, as a leadership change looms, it is unclear if the next president will do as much or more than the current administration. The economic and resource politics of Indonesia may evolve again – for example, if the next government allows plantation operators to expand and clear more land. There are gaps to be addressed going forward to both mitigate the outbreaks of fires and to provide incentives for sustainability.

Although Mr Widodo’s term is ending, political attention and will must be asserted to confront the current issues, if indeed this is to be an enduring legacy of his presidency that will endure.

Private sector action

Consider firefighting, a key response capability. Mr Widodo has once again mobilised the police and military to assist in firefighting, an important signal that he is taking matters seriously. But in many parts of Indonesia, the majority of firefighting capacity is in the hands of the private sector, not local governments.

Companies know they can be blamed for fires on their land, even ones they did not start, and most respond to fires within a 5km radius of their concessions as a condition of holding a business licence. Some are prepared to go further and help local communities be fire-free, with the support of local authorities.

Conservation and ecosystem restoration must be ramped up. This is especially needed for peatlands, which are wet in their natural state but can release the heaviest sooty haze and the most carbon when they are drained and burnt.

Created by Mr Widodo in 2016, the Peatland and Mangrove Restoration Agency has rewetted some 1.5 million ha of peat in public land – an area more than 20 times the size of Singapore. Additionally, companies have undertaken rewetting initiatives on nearly 3.7 million ha of peatland under an initiative supervised by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Such efforts are reported to reduce fire outbreak within rewetted boundaries.

But while significant ground has been covered, Indonesia is home to over 20 million ha of peatland and some estimates suggest that around half that area is in need of rehabilitation. There are also non-peat forest areas prone to fire that could benefit from conservation. Such a vast scale suggests government action cannot succeed on its own.

Local communities should be involved. Government agencies and several companies are currently helping villages by providing assistance and incentives to keep themselves fire-free. The lack of alternatives and income insecurity are what often drives farmers to use fire. These efforts should be further encouraged and supported to ensure that livelihoods are secured in tandem with sustainability efforts.

Some companies are going further, pledging to conserve carbon- and biodiversity-rich areas within their concession boundaries. This is commendable but needs support. The business licensing system in Indonesia should be flexible enough to allow companies to commercialise such projects and allow them to generate and sell carbon credits. This would provide stronger financial incentives to safeguard such areas against fires and degradation.

But even as incentives are needed, so too are the right forms of pressure to instil responsibility.

Investigations and prosecutions are the clearest forms of deterrence. After all, while dry conditions make matters worse, the vast majority of fires are human-started. Indonesian officials need to keep a keen and fair eye on the ground, cooperating with helpful companies and singling out the recalcitrant.

Over the past three years, Indonesia has also conducted audits of plantation sectors, searching for corruption and abuses. Further action is expected in the remaining months of the present government’s term to follow up on its governance push.

Can others help?

The Indonesian authorities may seem sensitive to criticism and zealous over sovereignty issues, but there is a case for more transparency, dialogue, and cooperation. In policing corporations, investigations may uncover investment, trade, and finance links to Malaysia and Singapore. If there is a request from Indonesia backed up by credible evidence, governments should cooperate for cross-border enforcement.

There are also wider links to climate change. In an ordinary year, forestry and other land use accounts for 30 per cent to 40 per cent of Indonesia’s annual emissions. In a severe haze year, the emissions from fires and the forestry sector can exceed the emissions from all other sectors combined. Stemming fires and preventing their recurrence could provide the basis for win-win cooperation on ecosystem conservation, including international investment in nature-based solutions and carbon credits.

In September, Indonesia launched its first carbon emissions trading market. While now focused on the power sector, Indonesia hopes to introduce a carbon tax in the future and encourage the wider buying and selling of carbon credits, including ones from forest conservation projects. Indonesia therefore has an incentive to keep carbon sequestered in its forests and be trusted to do so, rather than allowing trees and peat to burn.

At the regional level, Asean can play a supporting role. The grouping recently reached a final agreement to establish a permanent Asean Coordinating Centre for Transboundary Haze Pollution Control in Indonesia. It should facilitate better information sharing on haze situations, working with the existing Asean Specialised Meteorological Centre. The grouping is also rolling out a new haze-free road map for 2023 to 2030, along with an investment framework to support haze prevention projects.

There is also much to be done by the private sector outside of Indonesia. Increasingly, supply chains are subject to intense scrutiny, especially by developed markets and investors. Traders and financial institutions must map this sector more carefully to understand where the risks are and where efforts can be applied to improve practices.

The 2023 haze we have seen is not as severe as past instances. But unless actions are stepped up and then continued by the next government, the coming years could stain the efforts of the last decade and Mr Widodo’s legacy, leaving a darker grey in the skies.

Simon Tay is chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs (SIIA), where Khor Yu-Leng and Aaron Choo are respectively associate director and senior assistant director (special projects and sustainability).

This article is part of a series of SIIA column on “The Politics that Matter to Business” for The Business Times. It was first published on 11 October 2023.