By Chen Chen Lee and Lau Xinyi

The fight against climate change has notably taken a hit during US President Donald Trump’s first year in office.

Besides rolling back domestic policies and regulations from the era of his predecessor Barack Obama, Mr Trump also announced plans to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal.

Questions arise regarding America’s long-standing environmental leadership and what this may mean for Asia – a region highly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.

After all, the United States is the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs) worldwide, after China, and its Paris Agreement emission cuts would have contributed about 20 per cent of worldwide emission cuts foreseen by the agreement.

The country is also a significant source of finance and technology. Between 2010 and 2015, US$15.6 billion (S$20 billion) in climate finance was allocated across adaptation, clean energy and sustainable landscape activities.

Yet, regardless of the US’ leadership – or lack of it – in the coming years, Asia can be expected to move ahead on the environmental front for a few reasons.

First, many governments are not only showing a willingness to lead, but are also taking concrete actions to align economic and environmental goals.

In Vietnam, a National Committee on Climate Change is tasked to oversee climate change and green growth programmes. This committee is chaired by Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc and involves key ministers.

In addition, Indonesia’s Ministry of National Development Planning and the National Development Planning Agency plans to “synchronise its strategic development plans with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”.

The SDGs provide clear guidelines and targets for all countries with a view to eliminate all forms of poverty, combat inequalities and address climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind.

These leaders reflect a shifting mindset at a time when many economies face pressing concerns such as growing nationalist and populist politics, as well as rising cyber-security risks. Economic growth is increasingly viewed in the long-term, and Asian countries recognise the need to take greater ownership in fulfilling their international commitments.

Second, apart from governments, some companies are demonstrating a genuine interest to make an impact through their operations.

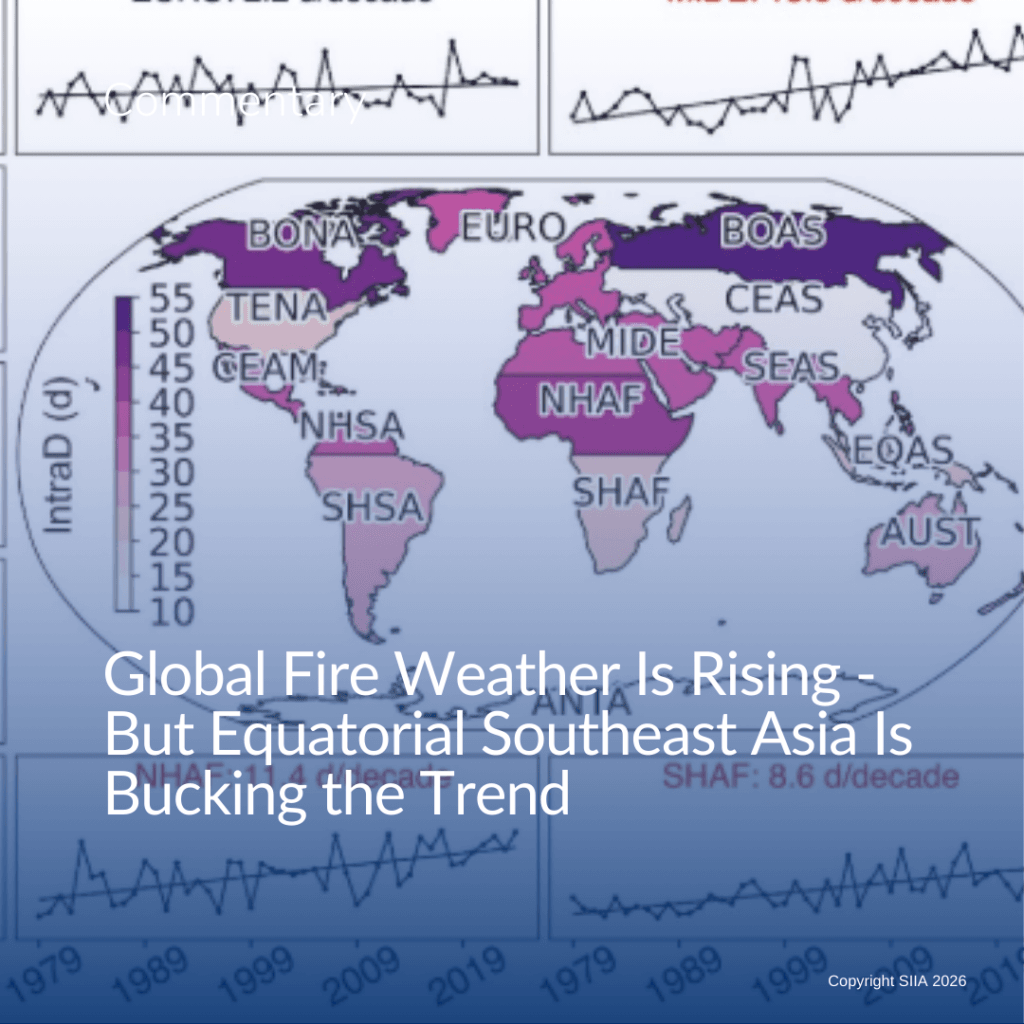

One area is in improving agricultural production practices in South-east Asia, thereby reducing incidences of land and forest fires. This in turn minimises the occurrence of transboundary haze pollution, which is associated with significant carbon emissions and poses a threat to public health.

For instance, in the palm oil sector, the South-east Asia Alliance on Sustainable Palm Oil was founded by major companies Unilever, Danone, Ayam Brand, Ikea and Wildlife Reserves Singapore. It aims to encourage more manufacturers and retailers to adopt sustainably produced palm oil, and offer consumers environmentally friendly options for the many products with palm oil. With more companies joining the alliance, the collective effort can help increase demand and improve the way palm oil is produced in other countries.

Moreover, as multinational corporations step up their commitments to fight climate change, this will have a ripple effect on their supply chains.

In fact, a 2017 report by World Wildlife Fund, Calvert Investments, CDP and Ceres noted that nearly half of the Fortune 500 companies have at least one climate or clean energy target to decrease their carbon footprints. When their supply chains are located in Asia, the environmentally and socially friendly practices of these companies could likewise benefit the host countries and raise the sustainability bar for local industries.

Third, the growing momentum to fight climate change is sparking more technology and innovations among different countries.

While China dominates the world in renewable energy expansion, smaller states such as Singapore are also doing their part to develop climate solutions. Besides implementing a carbon tax on large direct emitters of GHGs from 2019, Singapore is also seeing the rise of new business models for solar energy production and sales.

Over time, such developments help to drive down costs and make climate solutions more accessible to the masses.

Fourth, as the public and private sectors increasingly embrace green finance, more resources will be available to fight climate change.

Green finance promotes efficient capital flows to activities and projects which are more sustainable and responsive to climate concerns. Notably, the Monetary Authority of Singapore has included sustainability as an aspect of its supervision of banks. Local banks today are also more explicit in integrating minimum sustainability standards in their financing processes.

This is perhaps only the beginning. As financial centres worldwide align more closely with sustainable development, there is potential to bridge the climate financing gaps previously supported by the US and ensure that the world is not falling behind in its climate battle.

The pressing challenges of climate change mean that Asia must move on regardless of the US’ leadership. The signs are positive and only time will tell how much we have achieved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Chen Chen Lee is director of policy programmes and Lau Xin Yi is senior policy research analyst (sustainability) at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs. This commentary was originally published in The Straits Times on 27 January 2018.